Today’s post is a result of conversations I’ve had with a couple of author friends—and a situation I’ve faced myself. Suppose your plot demands that your protagonist has been charged with a crime. Maybe he’s even been convicted. But you also want to make sure that the protagonist remains a sympathetic character. You don’t want your readers to reject him due to his background. How can you pull this off?

One obvious answer is to make sure the readers know he’s innocent. The poor lamb has been wrongfully accused. This can make a juicy plot driver in itself, but it has also been done a lot (as in The Fugitive), and if not handled well can come of as trite.

I think there’s much more potential when your protagonist is actually guilty. He did the deed. Ah, but why? Maybe he was desperate. Maybe he was young. Maybe he foolishly let himself get pulled in by the wrong crowd. Maybe he had a really rough background and the crime seemed, at the time, his best choice. Not only are all of these realistic and interesting, but they also reflect true life: most criminals aren’t especially different from the rest of us. They just made some bad decisions.

It’s probably easier to rehabilitate your protagonist for some crimes than for others. It’s harder to sympathize with a violent offender, for instance. And some offenses, such as rape and child abuse, are probably just about hopeless. If your guy commits one of those, it’s unlikely you’ll ever endear him to readers. But never say never, I guess. Hannibal Lecter comes to mind.

Whatever crime your guy has committed, you may also face the issue of how to keep him from doing hard time. If it was a relatively minor offense and he didn’t have much of a record, you can probably get away with giving him probation. If someone else committed the crime with him, perhaps your guy will testify against him in exchange for immunity or a plea deal. If his circumstances were really extreme, he might even seek clemency (which in most states can be granted by the governor; the president can grant it for federal crimes). But in real life, clemency is an extremely rare event.

From 1901 until 1981, this was the Wyoming State Penitentiary (a new state pen eventually opened in the same town; that’s where Wyoming’s felons are now incarcerated). It must have been a miserable place to do time. In the early years, there was no electricity or running water, and our guide said the temperature inside was never more than 20 degrees warmer than the outside temp. Picture that during a Wyoming winter, when the thermometer regularly drops below 0F. Two or even three men would share a single 5 by 7 cell—which at least might have added a bit of body heat.

From 1901 until 1981, this was the Wyoming State Penitentiary (a new state pen eventually opened in the same town; that’s where Wyoming’s felons are now incarcerated). It must have been a miserable place to do time. In the early years, there was no electricity or running water, and our guide said the temperature inside was never more than 20 degrees warmer than the outside temp. Picture that during a Wyoming winter, when the thermometer regularly drops below 0F. Two or even three men would share a single 5 by 7 cell—which at least might have added a bit of body heat.

Garrote. This was used as an execution method in Spain and some Spanish colonies. The criminal’s neck was secured in the loop and the screw was tightened into the spinal cord.

Garrote. This was used as an execution method in Spain and some Spanish colonies. The criminal’s neck was secured in the loop and the screw was tightened into the spinal cord. The gibbet. This was used in a variety of ways. A living prisoner could be locked inside until he died of dehydration, exposure, or starvation. Or the body of an executed prisoner could be displayed. This was often used for pirates.

The gibbet. This was used in a variety of ways. A living prisoner could be locked inside until he died of dehydration, exposure, or starvation. Or the body of an executed prisoner could be displayed. This was often used for pirates. The rack. Technically, this was used to torture people rather than execute them. But death was a common result, either immediately or eventually, since the device dislocated limbs.

The rack. Technically, this was used to torture people rather than execute them. But death was a common result, either immediately or eventually, since the device dislocated limbs. The wheel. Criminals were tied to the wheel and usually all their limbs were broken. If they didn’t die right away, they might be left to die of exposure, shock, or dehydration.

The wheel. Criminals were tied to the wheel and usually all their limbs were broken. If they didn’t die right away, they might be left to die of exposure, shock, or dehydration. It’s debatable whether the iron maiden was ever actually used. This replica has rubber spikes, fortunately for me.

It’s debatable whether the iron maiden was ever actually used. This replica has rubber spikes, fortunately for me. Decapitation. Quick and easy, and doesn’t require much equipment. (I’m thankful to various Croatian tour guides and museum employees for encouraging me to play with their exhibits.)

Decapitation. Quick and easy, and doesn’t require much equipment. (I’m thankful to various Croatian tour guides and museum employees for encouraging me to play with their exhibits.) This is a restraint device called a scavenger’s daughter. The head went through that ring at the top, hands through the middle arches, and feet through the bottom loops. A few hours spent in that position would get very uncomfortable.

This is a restraint device called a scavenger’s daughter. The head went through that ring at the top, hands through the middle arches, and feet through the bottom loops. A few hours spent in that position would get very uncomfortable. The throne. A suspect could be attached to it in a variety of positions and then flogged or otherwise tortured.

The throne. A suspect could be attached to it in a variety of positions and then flogged or otherwise tortured. Interrogation chair. Okay, not the comfiest of seats, but not as awful as it looks. But it does look scary, and a suspect’s legs or arms could be smushed into the spikes.

Interrogation chair. Okay, not the comfiest of seats, but not as awful as it looks. But it does look scary, and a suspect’s legs or arms could be smushed into the spikes. Head crusher.

Head crusher. And the thumbscrew.

And the thumbscrew. See that pillar to the right of Spike? In Roman times, people would be tied to it and flogged; that space around it was essentially the main square. I took this photo in Zadar, Croatia.

See that pillar to the right of Spike? In Roman times, people would be tied to it and flogged; that space around it was essentially the main square. I took this photo in Zadar, Croatia. Branks were metal masks, often in the shape of animal heads. Some had metal flanges that went into the mouth. Branks were often used on women who were considered quarrelsome.

Branks were metal masks, often in the shape of animal heads. Some had metal flanges that went into the mouth. Branks were often used on women who were considered quarrelsome. Some people who violated religious norms might be required to wear these vests. I don’t know what the jellyfish-looking things are supposed to be.

Some people who violated religious norms might be required to wear these vests. I don’t know what the jellyfish-looking things are supposed to be. Branding was a more permanent way of identifying criminals.

Branding was a more permanent way of identifying criminals. This is a pillory. Some were stationary but some, like this one, could be driven around town. The offender might be flogged while he was locked in it.

This is a pillory. Some were stationary but some, like this one, could be driven around town. The offender might be flogged while he was locked in it. These are stocks. Which would actually be pretty ineffective for a prisoner with no legs.

These are stocks. Which would actually be pretty ineffective for a prisoner with no legs. This is Alcatraz, perhaps one of the most famous prisons in the world. It was a federal prison, housing those who were especially dangerous or high escape risks. But it was very expensive to run, so it operated as a federal prison for less than 30 years. We toured when my kids were younger, and they enjoyed. The littler one was especially taken with Al Capone’s story.

This is Alcatraz, perhaps one of the most famous prisons in the world. It was a federal prison, housing those who were especially dangerous or high escape risks. But it was very expensive to run, so it operated as a federal prison for less than 30 years. We toured when my kids were younger, and they enjoyed. The littler one was especially taken with Al Capone’s story. This is a recent photo of what was once the largest mental hospital in California, the Stockton Asylum. It opened during gold rush times and remained in use as a mental hospital until 1995. It’s now a university campus.

This is a recent photo of what was once the largest mental hospital in California, the Stockton Asylum. It opened during gold rush times and remained in use as a mental hospital until 1995. It’s now a university campus. This is a military jail (or gaol, I guess) in Edinburgh, Scotland.

This is a military jail (or gaol, I guess) in Edinburgh, Scotland. This jail cell is in Monterey, California. I think it’s interesting how closely it resembles the Scottish cell.

This jail cell is in Monterey, California. I think it’s interesting how closely it resembles the Scottish cell. These are the ruins of the gold rush-era jail in Coloma, California.

These are the ruins of the gold rush-era jail in Coloma, California. This gold rush jail is in better shape. It’s in Columbia, California. My younger daughter looks happy to be there, doesn’t she?

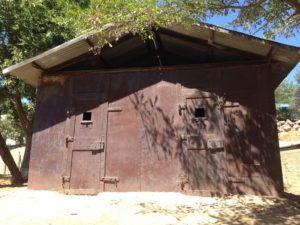

This gold rush jail is in better shape. It’s in Columbia, California. My younger daughter looks happy to be there, doesn’t she? This is also from gold rush times, and it’s in Knights Ferry, California. Summer temps regularly get above 100F there–imagine what it would be like locked inside those metal walls.

This is also from gold rush times, and it’s in Knights Ferry, California. Summer temps regularly get above 100F there–imagine what it would be like locked inside those metal walls. This jail is in a tower atop the city wall in Ulm, Germany.

This jail is in a tower atop the city wall in Ulm, Germany. One of those flags is flying over a cell in the castle wall in Lisbon, Portugal.

One of those flags is flying over a cell in the castle wall in Lisbon, Portugal. This cell was in the old city wall in Sarajevo, Bosnia & Herzegovina.

This cell was in the old city wall in Sarajevo, Bosnia & Herzegovina. And this one (which contains my daughter in the photo) is in beautiful Dubrovnik, Croatia.

And this one (which contains my daughter in the photo) is in beautiful Dubrovnik, Croatia. Finally, another German cell, in Rothenburg.

Finally, another German cell, in Rothenburg. So here’s your plot bunny. Your character is an attorney representing a smooth bad guy. The bad guy lies on the stand—implicating someone else—and is found not guilty. Now the cops are after that third party, and your lawyer wants to make sure an innocent party doesn’t go to prison. What does he do? And what complications might ensue if he’s attracted to that innocent third party?

So here’s your plot bunny. Your character is an attorney representing a smooth bad guy. The bad guy lies on the stand—implicating someone else—and is found not guilty. Now the cops are after that third party, and your lawyer wants to make sure an innocent party doesn’t go to prison. What does he do? And what complications might ensue if he’s attracted to that innocent third party?